When one thinks about Cambodia, two things often come to mind. The first is Angkor Wat, an ancient temple complex built during the Angkorian period from the ninth to 15th centuries. The Angkorian period featured a powerful and vast Khmer Empire that was highly cultured and produced magnificent art and architecture. For many Cambodians, this period signifies the pinnacle of their civilization.

The second thing that often comes to mind evokes a starkly different set of images: the period of the Khmer Rouge, which ruled the country from 1975 to 1979. This regime tried to purify the nation of suspected corruption and counter-revolutionary tendencies in order to bring about its utopian communist vision for Cambodia. But the regime’s ideology and tactics were so extreme that it targeted almost all aspects and segments of Cambodian society for destruction, and was ultimately responsible for the deaths of an estimated two million of the country’s seven million people.

Map 1: Cambodia and Its neighbours.

The second half of the 20th century was a period of radical change for Cambodia. The first part of this story begins in the aftermath of a revolution and a war of independence against the French in 1953, and ends in 1979 with a country that was traumatized, starving, and littered with landmines and the remains of people who had perished over the previous four years. In the 26 years in between, Cambodia cycled through several different governments, political systems, and sweeping social and cultural changes ushered in by war, modernity, globalization, and a radical communist ideology. And throughout these turbulent episodes, various alliances between rival factions and their leaders were formed, severed, and formed again.

The second part of the story is still being written. It is about how the people of Cambodia, since 1979, have sought to rebuild their lives and communities and to heal from the past. It is also about finding truth and accountability for those both in and outside the country who caused, enabled, or ignored one of the worst genocides of the 20th century.

Cambodia had been a colonial subject since 1863, when King Norodom invited France to serve as the country’s protector. The king did this in an effort to free Cambodia from the predations of the neighbouring Thai and Vietnamese, who had repeatedly attacked Cambodia and threatened its existence. The French colonial presence, the king believed, would offer Cambodia respite and relative peace and security.

The legacy of French colonialism – specifically, how it influenced social and political thinking in Cambodia – is mixed. On one hand, the French introduced Cambodians to ideas about nationalism and modernity that began to take root in the early part of the 20th century (although it was not the intention on the part of the French to instil in their colonial subjects a sense of nationalism). One of the most significant ways this happened was by giving scholarships to young, educated Cambodians from middle-class and elite families to attend universities in France. On the other hand, the French failed to bring education to the vast majority of people back in Cambodia; in fact, prior to independence, the country had only one high school.

The movement for independence from France emerged amid the chaos of the Second World War and early post-war period. This movement, called the Khmer Issarak, was a loose coalition of anti-French, anti-colonial activists with support from the Thai government and the Viet Minh, communist allies in neighbouring Vietnam. But the group’s cohesiveness soon began to fray, and the movement split between those who sided with the Viet Minh and those who fought against them. Among the movement’s members were a new elite intellectual class, some of whom had been part of the group that studied in France in the late 1940s and early 1950s. This included Saloth Sar (who later became known as Pol Pot), Son Sen, Ieng Sary, and Ieng Thirith (Ieng Sary’s wife). These individuals would later become leaders of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, more commonly known as the “Khmer Rouge,” meaning red/communist Khmer. (Kampuchea is another name for Cambodia, and Khmer is the name of the main language and ethnic group in Cambodia.) In addition to embracing ideas of nationalism, these future leaders also studied the communist teachings of Lenin and Marx, which shaped their ideas and plans for their nation’s future.

As Cambodia was trying to find its footing as a newly independent country, the dynamics of the Cold War were already in full swing. In the scramble for power and security, the U.S., the Soviet Union, and China all struggled for influence and control over smaller countries. One of the places where this competition was most intense was Southeast Asia. Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos, which were collectively known as Indochina under French colonialism, became enmeshed in this struggle as they wrestled free from colonial rule.

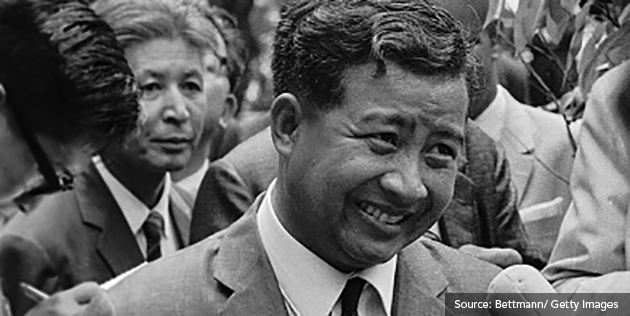

After Cambodia achieved its independence in 1953, the country’s king, Norodom Sihanouk, gave up his crown to his father so that he could become Cambodia’s head of state. Sihanouk was a charismatic character with a taste for writing, music, and especially filmmaking. He was also ever adaptable to the changing tide that continuously swept through his nation. Many Cambodians generally recall the Sihanouk period as a time of harmony and co-operation, and he did much to expand education in Cambodia and build up and modernize the capital city of Phnom Penh.

Figure 1: Prince Norodom Sihanouk.

But his 17 years of rule were also a time of vast corruption and social and economic inequality. The division between the urban areas and the countryside became more severe; while the cities developed into modern cosmopolitan meccas offering education and opportunities to their residents, life in the countryside for the much larger number of peasants was relatively unchanged. In addition, the Cambodian government under Sihanouk did not tolerate ideological and political dissent, including dissent by communist groups that were forming within the country.

In addition to his mixed record in managing Cambodia’s internal affairs, Sihanouk’s success in handling the larger global forces swirling around his small kingdom were also mixed. His period of rule roughly coincided with the Second Indochina War, also known as the “American War” in Vietnam and as the “Vietnam War” in many Western countries. This conflict began in 1955, escalated in the 1960s, and ended when the U.S. withdrew from South Vietnam in 1975. This conflict was a proxy war between North Vietnam, which was supported by the Soviet Union and China, and South Vietnam, which was supported by the U.S. and other non-communist allies.

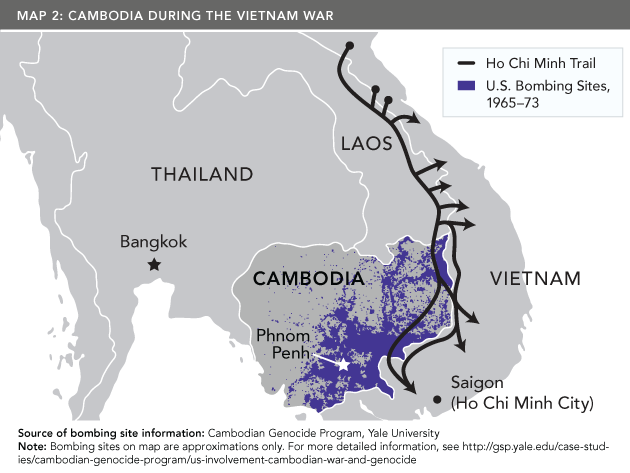

The North Vietnamese, under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh, sought to create bases and supply trails through Laos and Cambodia in order to send troops and supplies to their supporters in the south. This route became known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. While this was happening, Vietnamese communist forces also sought to support Cambodia’s communist movement, which included the Khmer Rouge. The U.S. became increasingly enmeshed in this war through successive presidencies; shortly after he took office in early 1969, President Richard Nixon launched a secret bombing campaign, code-named Operation Menu, aimed at destroying North Vietnamese bases and supply lines that were being run through Cambodia (see Map 2).

Map 2: Cambodia during the Vietnam War.

Through the tumultuous post-independence years, Sihanouk pursued a policy of neutrality between the communists (i.e., the North Vietnamese and China) on one side and the Americans on the other. At the time, however, some had suspected that he was showing preference to the communist cause by allowing the North Vietnamese to set up bases within Cambodia. Amid these growing political tensions, Sihanouk was ousted in a bloodless coup in 1970 while he was out of the country. The man who replaced him was his prime minister, Marshal Lon Nol. The U.S. had been unhappy with Sihanouk’s compliance with the North Vietnamese and supported the change in leadership.

The Khmer Rouge, with support from the North Vietnamese, were already fighting in the Cambodian countryside and eventually began taking control of territory from the Lon Nol government. Other renegade groups of Cambodian fighters were also engaged in the struggle for control of the country. Adding to the violence and chaos in the countryside, in 1973, the U.S. escalated its bombing campaign in Cambodia, now code-named Operation Freedom Deal. Out of a total of 500,000 tons of explosives dropped by the U.S. military on Cambodia from 1969 to 1973, roughly half were dropped within a seven-month period in 1973. (By comparison, the U.S. dropped approximately 180,000 tons of explosives on Japan during the Second World War.) Many times, the American B-52 bombers missed their targets, resulting in the death and destruction of entire Cambodian villages. While estimates are unclear as to the number of Cambodian deaths that resulted from these bombings, they range between 50,000 and 300,000. 1

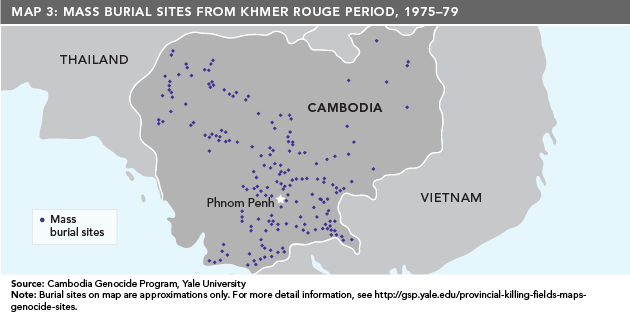

Map 3: Mass burial sites from Khmer Rouge period, 1975-79.

Unsurprisingly, the bombing fostered anger and fear among the Cambodian people, driving some from the countryside to seek shelter in the capital city of Phnom Penh. Others joined the Khmer Rouge, whom the Cambodians believed were fighting on their side because of the Khmer Rouge’s promises to secure more rice and to alleviate taxation and other burdens and limitations imposed on them. But there was another significant factor in nudging more Cambodian peasants towards the Khmer Rouge: after Sihanouk was overthrown in 1970, he joined the Khmer Rouge from exile in China and, through a radio broadcast, called on his fellow Cambodians to join him. Given his widespread influence and appeal, many people, especially from the countryside, heeded his call, thereby encouraging the Khmer Rouge’s eventual rise to power.

Of course, not all people freely chose to join the Khmer Rouge. When the Khmer Rouge took control of an area, they would simply draft those old enough to fight or serve the movement in other ways. To resist would mean death. By 1973, the Khmer Rouge had gained control of most of the countryside and started requiring villagers to live in co-operatives and engage in large-scale agricultural projects. 2 They also began executing people whom they accused of being traitors.

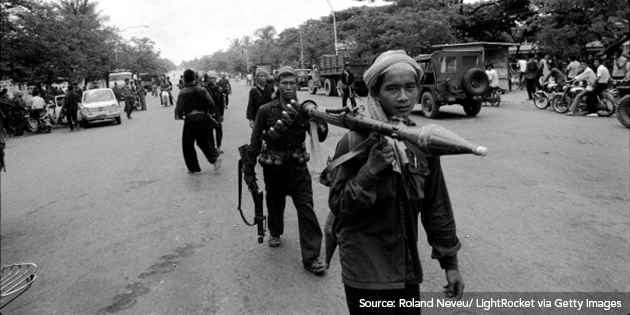

As the majority of the countryside came under Khmer Rouge rule, the situation in the capital city of Phnom Penh became increasingly dire. The city’s population continued to swell, and food was running scarce as rice production was disrupted due to the civil war and the blocking of supply routes by the Khmer Rouge. The Lon Nol government could no longer hold its ground against the Khmer Rouge, especially after the U.S. ended most of its bombing after 1973 and the South Vietnamese withdrew from Cambodia, leaving Lon Nol’s government troops to fend for themselves. The last helicopter carrying the remaining U.S. citizens and a number of high-ranking Cambodians left on April 12, 1975. Five days later, the Lon Nol government collapsed and Khmer Rouge soldiers marched into Phnom Penh.

The teenage Khmer Rouge soldiers who took the city – uneducated, hardened by war, and loaded with weapons – were alien to the city’s sophisticated residents. Initially, some in Phnom Penh expressed relief that the war had come to an end. But any sense of relief they felt quickly vanished. Khmer Rouge soldiers ordered the city’s residents to evacuate their houses immediately and head to the countryside. The rationale they gave was that now that they had taken over the capital, the Americans would most certainly bomb the city. The residents were given no time to pack and were ordered at gunpoint to leave. There were no exceptions. Patients were dragged from their hospital beds and women were forced to give birth along the road. The young, the old, the frail, and the sick all had to keep moving or risk being shot. Under the scorching hot April sun in Cambodia, many who were frail died along the road, their bodies left to swell in the heat.

Figure 2: Khmer Rouge soldiers march into Phnom Penh, 1975.

Both city residents and those in the countryside were assigned to work in agrarian labour camps to grow rice and build dams and dikes, or work on other agricultural projects. The Khmer Rouge, known only as Angkar (“the organization”), also sought to eliminate all vestiges of the previous regime that they considered corrupt or dangerous. Their idea was to wipe the slate of society clean so they could start over in building a new society at “year zero.” This meant the abandonment and destruction of cars, jewelry, money, clothes (that were anything other than the farmers’ typical black clothing), radios, books, personal items of any kind, and anything that represented wealth, class, or individuality.

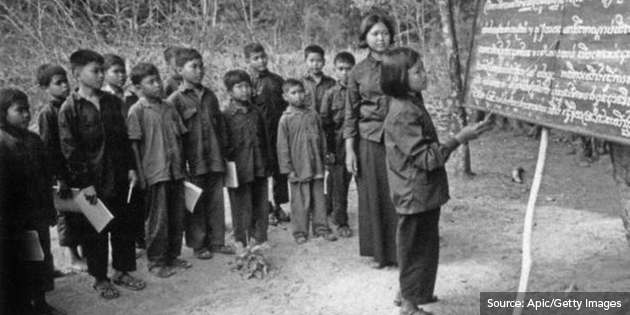

In addition to eliminating personal property, the Khmer Rouge were also determined to root out ideas that were considered counter to their revolution. This included religion, education, and knowledge. They closed schools, destroyed libraries and temples, and banished religion. But even that was not enough; in their desire to purify the nation from all dissent and corrupting elements, they also annihilated anyone deemed a threat. For example, when Khmer Rouge soldiers seized Phnom Penh, they quickly executed government and military leaders. They also targeted the wealthy, the educated, and the religious for eradication. The urbanites who managed to survive this initial round of executions quickly learned to conceal their education and to avoid displaying manners that might be associated with the higher classes.

The set of beliefs that shaped life under Democratic Kampuchea, which was the formal name given to Cambodia by the Khmer Rouge, drew from Marxist-Leninist and Maoist thought and integrated communist ideology with pre-existing Cambodian religious and cultural ideas. The result was a utopian philosophy that sought to free Cambodia from dependence on other nations. In 1976, one Khmer Rouge cadre wrote in a notebook that the aim of the revolution was to create a ”national democracy and revolution that provides rice fields for the masses” and to rid the nation of all forms of feudalism, capitalism, and imperialism. 3 This revolutionary program required that individuals be ever vigilant against enemies of the revolution. As a result, the Khmer Rouge employed spies to report on any activities that might be interpreted as countering the ambitions of the revolutionary movement.

Figure 3: Learning about agricultural methods under the Khmer Rouge.

The degree of distrust within Democratic Kampuchea became all-pervasive as more traitors were “discovered” and increasing numbers of real or alleged associates were identified in forced confessions. As “enemies” of the Khmer Rouge revolution were arrested and tortured into confessing their allegedly traitorous activities, they were also required to supply the names of people they were associated with and who were part of their supposed “network.” 4 “In the manner of a self-fulfilling prophecy, the distrust was sustained, rationalized, and reproduced, creating a warped logic whose conclusion could only be total annihilation." 5

By 1977, the distrust on the part of the leadership had reached paranoiac heights and the purges of suspected traitors increased. Even the ranks of the Khmer Rouge cadres themselves were purged, sending increasingly larger numbers of them and their families to prisons where they were tortured and then murdered. The most notorious of these prisons was S-21, a high school in Phnom Penh that was converted into a prison and torture centre run by Kaing Guek Eav, also known as Duch. 6 Out of an estimated 15,000 prisoners who were sent to S-21, only seven survived. Prisoners housed there were photographed and tortured to produce confessions. When the interrogators were finished, the prisoners’ corpses were carried by truck to the “killing fields” outside of Phnom Penh. There are approximately 20,000 of these mass graves in various locations in the country. 7

The years of the Pol Pot regime had been a living hell. The people who endured it survived on a ladle of watery rice gruel a day and were subjected to forced labour for most of their waking hours. They were separated from their families, forced to eat in co-operatives, and treated worse than the farm animals. Life under the Khmer Rouge was lived in constant terror of being reported for even minor acts, such as taking a coconut from a tree or allowing cattle to graze in the wrong field. Massive numbers of people, both peasants and urbanites, died as a result of these conditions. The Cham Muslim minority and ethnic Vietnamese minority groups were particularly singled out for persecution and annihilation. And the urbanites certainly suffered harder work and greater suspicion than did the peasants. In the end, an estimated two million men, women, and children perished under the regime.

But by 1977, there were also skirmishes breaking out between the Khmer Rouge and Vietnam, which by then was under the control of its communist government. By December 1978, Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia and overthrew the Khmer Rouge and their Democratic Kampuchea in January 1979. In its place, they installed a new Vietnam-friendly government, the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK). Khmer Rouge leaders and many of their followers fled to the Thai border where they sought refuge and continued their fight against the Vietnam-backed PRK. The United Nations voted not to recognize the new government in Cambodia, and instead Cambodia’s seats went to the Khmer Rouge, who were still aligned with Norodom Sihanouk and a non-communist political party.

In the early years after the fall of Democratic Kampuchea, the people of Cambodia were starving, traumatized, and scattered across the country. Some had escaped the regime earlier and were now in refugee camps in Thailand and the Philippines. Families were separated and often had no idea whether their sisters, brothers, parents, or spouses were alive or dead. For many, the homes where they once lived no longer existed. The country’s infrastructure was in ruins, and the once beautiful capital was an urban wasteland of blackened and bombed buildings not fit for habitation.

Figure 4: Cambodian refugees, 1979.

In 1979, Pol Pot, the leader of the Khmer Rouge, and Ieng Sary, a member of his inner circle, were tried in absentia by the PRK government for their crimes during Democratic Kampuchea. They were found guilty of genocide, but there were no sentences given. This did not mean that the Khmer Rouge surrendered; in fact, many of its soldiers and leaders continued to fight, and the struggle to bring out the truth and some sort of justice and reconciliation would take many, many more years.

To learn more about what happened after the genocide and how Cambodians have tried to reconcile, go to the PDF above.

End Notes:

1 The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) website puts the number at around 300,000, and the Cambodian Genocide Program at Yale University at 50,000 to 150,000.

2 The Cambodian Tribunal Monitor website states that in early 1973, 85 per cent of the countryside was controlled by the Khmer Rouge.

3 D2183 - Srei Ha 1976, Khmer Rouge Cadre Notebook.

4 Many of these confessions remain in the archives at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Cambodia. For a rigorous and compelling analysis of the torture and confessions at Tuol Sleng, see David Chandler, Voices from S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot’s Secret Prison, 1999, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

5 Eve Zucker, Forest of Struggle: Moralities of Remembrance in Upland Cambodia, 2013, University of Hawaii Press. Page 54.

6 Duch’s trial was the first held at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia.

7 The Documentation Center of Cambodia lists 19,733 mass grave sites.